Despair for All

"Deaths of Despair" is a flawed framework for understanding what ails America in the 21st century.

Alright, apologies for the false start earlier today. This is the deaths of despair post based on this new Lancet paper out today.

*

You’re probably by now well aware that deaths from overdose, alcohol, and suicide are collectively labeled as “deaths of despair.” For the past seven years, the popular deaths of despair framework has been the go-to explanation behind a variety of health, social, and existential ills plaguing middle-aged, low-income, and low-educated white Americans.

Deaths of despair theorizes that this surge in mortality is driven by a Durkheimian anomie, the fraying of social bonds and the loss of meaning and purpose among a vast swath of people. Deaths of despair has even been used to shed light on the rise of the right-wing populist movement of “forgotten people” that propelled Trump to the presidency. The deaths of despair theory became so popular that contemporary use of the word “despair” has spiked.

But there’s some glaring problems with the deaths of despair story. Namely, the story goes that surging mortality driven by suicide, alcohol, and overdose is unique among low-income and low-educated white people. But that’s only true if other groups, such as Black people and Native Americans, as well as young white people with college degrees, are completely ignored.

“Not only do Native American communities have the highest rates of midlife mortality from the causes of deaths of despair, but these realities are also almost entirely missing from a set of powerful mainstream narratives about health inequalities told through the deaths of despair theory,” write the authors of a new analysis titled “Deaths of despair and Indigenous data genocide,” published Jan. 26 in The Lancet.

The new paper, authored by Joseph Friedman and Helena Hansen of UCLA, and Joseph P. Gone of Harvard, shows that if staggering levels of mortality among Native Americans and Black people were included in original and subsequent “deaths of despair” analyses, then that would drastically change the supposed unique and exceptional nature of midlife mortality among rural white Americans.

I’m making this long post free because I think it’s really important. Your financial support makes this possible, so please subscribe.

The deaths of despair framework was first articulated in a 2015 paper by Anne Case and Angus Deaton published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. Their paper has been cited many thousands of times both in academic literature and the popular press. Case and Deaton’s analysis landed at just the right moment. Deaths of despair became a skeleton key in a liberal discourse that was struggling to unlock the beliefs and behaviors of white, rural Americans who supported one Donald J. Trump for president. Indeed, demographic research showed that counties with excess mortality from alcohol, suicide, and overdose—“despair”—disproportionately voted for Trump.

New York Times opinion colunnist Paul Krugman immediately ran with Case and Deaton’s analysis in a November 2015 column titled “Despair, American Style,” in which the liberal economist tried to tease out the causes and conditions of “this epidemic of self-destructive behavior” ripping through rural America

Krugman writes, “There is a darkness spreading over part of our society. And we don’t really understand why.” Krugman asks whether a “materialist explanation” centering income inequality and a hollowed out middle-class might explain what’s going on. He quickly concludes: No, not really, it’s more complicated than that vuglar Marxist alienation stuff. Krugman cites Angus Deaton’s own explanation, one that is rather hard for an economist to prove or disprove, which is that middle-aged whites have “lost the narrative of their lives.” (and which econometric variable captures “the narrative of our lives”…?;)

For a taste of vulgar Marxism, in case you’re wondering why Krugman and Deaton might share a similiar worldview, both men are winners of the Nobel Prize in economics.

The deaths of despair explanation fit right in with an already existing story told by Trump’s campaign, a story about his “forgotten people” who were left behind. Trump would validate their wishes and hopes, but more importantly, he would tell them that their anger, resentment, and grievences are correct and justified. Mexicans are ruining the economy. Elite out of touch liberals in big cities hate you and destroyed your way of life. Both major political parties have sold you out. Trump told the people dying of despair who their enemies were and promised to publicly shame and embarrass and defeat them everyday. I’ll be your champion.

In other words, Case and Deaton’s story of despair gelled with the same liberals who looked to a guy like J.D. Vance, author of the book Hillbilly Elegy, to teach them about low-educated white people living in small towns. Liberal pundits and intellectuals now had their framework, their charts, and their narrative to explain how a guy like Trump, who to them was a complete fraud, a narcissist, a carnival barker for a death cult, could be so beloved and popular among those other people who dwell in America’s Heartland, a place alien and exotic, backward.

Whose Despair?

The truth is that deaths of despair are hardly unique to rural, white people. The “loss of a way of life,” the fraying of social bonds—is this really a white and rural phenomenon?

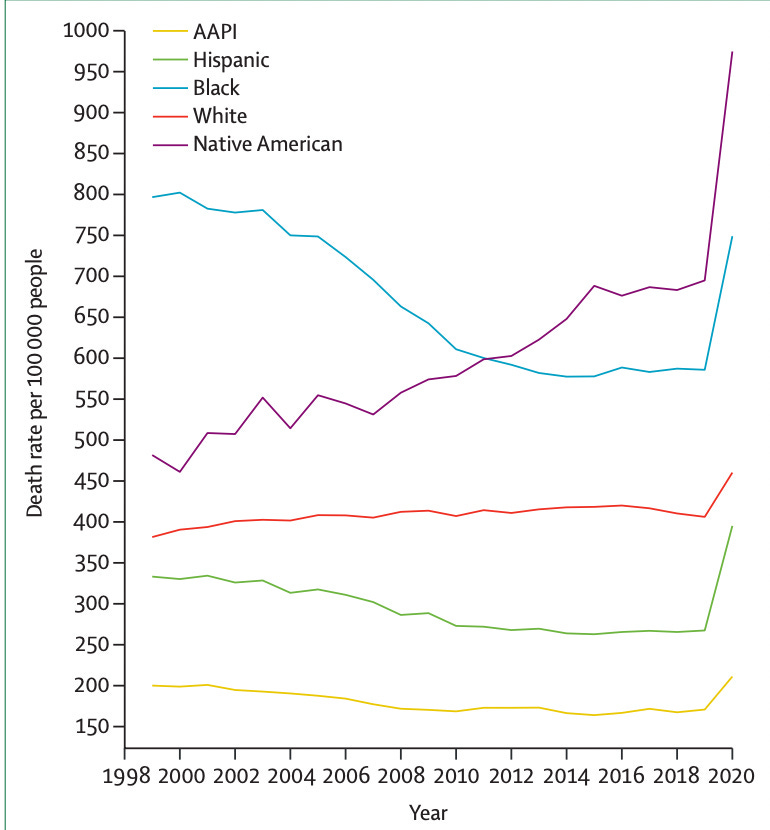

In The Lancet, Friedman, Hansen, and Gone write that, “Mortality from overdose, suicide, and alcoholic liver disease have collectively been higher among Native Americans than their White American counterparts in every available year of data since 1999.” What about Black mortality? “Although White mortality increased by about 30 deaths per 100,000 people in the early 2000s, this is small compared with the approximately 200 per 100,000 midlife mortality disadvantage faced by Black people.”

Case and Deaton’s analysis excludes these trends to make the case that something unique is happening to low-income white people without a college degree. Why exclude other people’s despair?

Case and Deaton’s original study analyzed mortality data from 1999 to 2013, a time when mortality rose from 381.5 per 100,000 to 415.4 per 100,000 in non-hispanic whites (an 8.9 percent increase). During that same time, Native American mortality rose from 481.6 to 622.7 per 100,000 people (a 29.3 percent increase). “This increase was more than three-times greater than the observed increase among White Americans.

These aren’t the only omissions by Case and Deaton. In their 2020 book, “Deaths of Despair and the Future of Capitalism,” Case and Deaton ignore many other contradictory trends that, when taken into account, undermine their story.

“Though they claim that deaths of despair are almost exclusively concentrated among middle-aged white people without college degrees, they never actually prove that point,” Erik Baker, a lecturer in the History of Science Department at Harvard, writes in an essay titled “Other People’s Despair” published in The Drift. (I love The Drift , by the way, and I highly recommend supporting them).

Like in the new Lancet analysis, Baker lays out how Case and Deaton ignore thorny data that poke holes in their story: “A number of their own graphs show an unmistakable rise in suicide and drug and alcohol mortality among white BA-holders since 2000 and among Black people without a BA since the early 2010s.” “Astonishingly,” Baker added, “the explosion in suicide among young people nationwide receives only a single vague mention.”

Indeed, my own life fits into one of those omitted categories. I come from an affluent and well educated suburb north of Chicago. I finished high school, got my bachelors, and also got a pretty pointless master’s degree on top of it. Oh, and I also used heroin in the early 2010s. Case and Deaton’s idea of despair never really explained why I or so many others in my class used opioids. I aslo don’t think it explains why my friends died from overdoses, friends who were also young, priveleged, and educated. We clearly lived different lives than the middle-aged white guy in Kentucky who didn’t go to college, and yet there was something similiar happening to us.

Why did my friends and I who were born into great material advantage use opioids in the mid-2000s while we were in high school? “Despair” doesn’t really explain it. First, pharmaceutical-grade drugs were abundant. Actually, they were fuckin’ everywhere! It was easier for us to get our hands on Xanax, Adderall, and OxyContin than alcohol or even weed. That was true in our little suburb of Chicago. That was doubly true in Kentucky, where pill mills flooded the entire Appalachian region with pills. That is not a function of despair. This happened because America’s drug and health care system is so deregulated that, in the early 1990s, some pharma company could have invented a 10,000mg oxycodone pill and it would’ve been greenlit for the market.

Case and Deaton’s understanding of drugs and addiction has alway felt a bit off to me. Who could blame them? They’re old Ivy Leaguers (Deaton is 77 years old!). This is not to toot my own horn, but Case and Deaton cited something I wrote for Slate in their book:

“In the words of a heroin user in recovery [me!], addiction ‘tends to start (obviously) with liking the feelings that drugs produce (warmth, euphoria, belonging) or the erasure of other feelings (trauma, loneliness, anxiety)—usually both at once.”

They use my quote to try and explain why they grouped suicides, alcohol use, and opioids together, when, on their face, all of these things are actually quite different from one another. And yet this grouping is foundational to their analysis, and it’s recieved scant attention or pushback. Is it not a pretty big leap to suggest that people who drink alcohol and use opioids are all suicidal? (To be sure: some number of suicides are misclassified as accidental overdoses, but we have no idea how many).

I was addicted to opioids and I was never suicidal. The only time suicide had ever remotely entered my mind was during hellish withdrawals. But that was acute. Fleeting. I didnt’ despair. Despair is the absence of hope. I had hope that I could actually get better, that a life worth living was still possible for me, and, I think, that is a big reason why I’m here writing this today.

Sure I was anxious, depressed, confused, and alienated in all sorts of ways that teenagers are. But I didn’t use opioids because I wanted to die. It’s actually the opposite. I wanted to live and opioids helped me do that. Opioids, at least in the beginning, made my life feel OK. I was more talkative, more likeable. I could do chores and homework. They helped me focus and concentrate. I got A’s on all my book reports and writing assignments because I could take some Norco, read for hours, and then sit my ass in a chair and comfortably write a lot. Opioids brought me a sense of calm and clarity, a warm energy that made me feel at ease and confident in myself. Of course, that’s the honeymoon period. Eventually things go dark.

Case and Deaton’s deaths of despair posits that midlife mortality, especially among middle-aged and low-educated white people, is caused by drugs, alcohol, and suicide, and that people used these substances and methods of dying because they’ve “lost the narrative of their lives.” This may very well be the case for some middle-aged white people, but it certainly isn’t what my life was like in high school.

Case and Deaton’s analysis just doesn’t apply to me nor my whole generation of opioid users. The story of our drug use isn’t that sociologically dramatic. The drugs were accessible and we liked them—a lot.

When I think of my generation dying en masse, I don’t think despair is to blame. I’ve focused on my journalism on the drug war and the American government’s response to the “opioid epidemic” because, in my mind, that’s a much more important driver of overdose deaths.

When millions of us got hooked on pharmaceutical opioids—thank you de-regulated, private, for-profit health care!—the government ripped the carpet out from under us, and that’s when overdose mortality really began to soar off the charts and break records year-after-year. I believe to this day that had my friends not suddenly lost access to regulated, FDA-approved opioids, that they wouldn’t have died from heroin or fentanyl of highly variable and unknown purity. This has little to do with despair and much more to do with bad policy being decided by incompetent people.

What about non-white overdose mortality? Native Americans across the country and older Black men in American cities have seen steep rises in overdose deaths, especially after illicit fentanyl took over the heroin markets. Some people thought Black people were somehow “spared” from the overdose crisis because doctor’s are too racist to prescribe them opioids. But that’s absurd and never made sense. Black people were discriminated against in white market settings, so they got their opioids in the illicit markets, where many of them fatally overdosed.

Obviously I cannot speak to the Black or Native American experience in as much detail as I can speak to my own. I’m a white Jewish guy from the suburbs. But from studying history, knowing a thing or two about mass incarceration, and after years of covering the drug war, I can say with confidence that their “despair” has been felt much harder and for much longer than most anyone else’s. Their mortality is higher. Their life expectancy is lower. Their economic life is harsher. So it’s completely strange to me for these groups to be excluded from the deaths of despair story when their mortality and life outcomes are objectively worse than white peoples.

When overdoses, alcohol use, and suicide rise among white people, the cause, the preferred story, was one of socioeconomic decline. A sympathetic story was about their plumetting quality of life. How they were promised the American Dream and were given something hollowed out and shitty and broken. Instead of a quality education, a union job with good benefits and an income to support a family, they got cheap TVs, fast food, and preacrious employment in the “service” sector. This, Case and Deaton argue, primed them and made them susceptible to substance use disorders and suicide.

Yet when Black people in Harlem suffered from a heroin epidemic in the 1970s, in the midst of rapid de-industrialization and poverty that hit Black communities hardest, their behavior was pathologized as criminal. From the 1980s onward, they were punished severely under harsh mandatory minimum sentences and overtly racist and discriminatory drug laws enforced by brutal over-policing.

Despair is indeed everywhere. But it’s specific, and particular. Despair isn’t just felt, it’s not an emotion that just arises out of being sad. Despair is the absence of hope. Despair takes root, forming dark lines and dreaded contingencies spreading outward and forward out of history. Despair doesn’t just rain down one day. Despair happens to people. Something, someone, causes despair.

When Covid hit, mortality rose and life expectancy dropped even steeper for everyone. But long before the pandemic, death rates for American Indian and Alaskan Native communities were dire. From 1999 to 2009, their death rates were 50 percent greater than those of non-Hispanic whites. Their suicide rates were also 50 percent higher.

To understand the Native American story of despair, I highly recommend reading an LA Times story titled, “How a remote California tribe set out to save its river and stop a suicide epidemic.” I’m immediately struck how the fate of The Yurok people in this story is profoundly tied to nature.

“Deep in California’s coastal woods near the Oregon border, the reservation straddles the mighty Klamath River, the tribe’s lifeblood for centuries.

But over the last 50 years, the yearly migration of salmon from the Pacific dwindled, and poverty, addiction and lawlessness gripped the reservation.

Last year, a rash of suicides pushed the tribe, California’s largest and one of its poorest, into an existential crisis….It would be a vastly complex task to slow the spiral of joblessness, broken families and addiction, intertwined as it was with the long demise of the river that once sustained everyone here.”

As the river died, so did the Yurok people. The river at the center of their life turned into a toxic algae green from too warm and too shallow waters. Commerical fishing upstream caught most of the salmon. Their story of despair is about the destruction of nature and denaturalization of human life. Wouldn’t we all despair if this happened to us? Case and Deaton say rural America lost the story of their lives. Maybe. But that feels most true for indigenous communities. But their losing isn’t passive. Their life was stolen. Their lives are being stolen.

From The Lancet paper:

“By 2019, midlife Native American mortality had risen further to 695.0 per 100,000 people, and in 2020, mortality increased precipitously to 974.7 per 100,000 people. These rates are 71.1% and 111.8% higher than the midlife mortality seen among White Americans in 2019, and 2020, respectively.”

In 2020, “Native American midlife mortality from deaths of despair-related causes were now over double that seen among White Americans,” Friedman, Hansen, and Gone write in The Lancet. Deaths of despair are objectively higher among Native Americans than for anyone else. And it’s a bit unbelievable to think that their despair isn’t driven by the material conditions of their life, and the destruction of their way of life.

To wrap this up, I’ll tell you why I think It’s important to scruitinize Case and Deaton’s “deaths of despair” story.

• First, because this framework has had such an outsized role explaining numerous public health emergencies and social ills across America. From the jump, this analysis has led many observers to think that overdose deaths, alcohol use, and suicide are problems unique to rural, white, and low-educated Americans. That’s just not true. And it’s weird to turn their despair into something exceptional and different from everybody else’s.

• Second, Case and Deaton’s deaths of despair story obscures where the action really is. Their story of despair and how to address it obscures more than it clarifies. Baker put it best in The Drift:

“[Case and Deaton] don’t support a universal basic income, because they think working-class communities need more of the salvific power of work, not less. They don’t support taxes on the wealthy, because their statistics supposedly prove that inequality itself is not a problem. At one point they simply pronounce that ‘a rebirth of unions is unlikely.’ Alas. They are in favor of ‘a modest increase in the minimum wage,’ but mostly they are in favor of vague platitudes like ‘making capitalism stronger by extending markets, rather than by undermining them.’”

If deaths of despair is such a dire crisis, then why are Case and Deaton’s prescriptions so tepid and weak? Case and Deaton go out of their way to sidestep material explanations for white people’s despair while centering existential, cultural, and religious ones. Case and Deaton tie themselves into knots trying to argue that a nicer version of capitalism would make people despair less.

• Third, and finally: America is built violently racist institutions and structures, from the drug war to mass incarceration, to a harsh economic life and privatized health care supported by our politicians, all of which produces untold and unmeasurable levels of despair. For everyone. But obviously so much more Black, Indigenous, and Latinx families. In their book, Case and Deaton acknowledge, “Black mortality rates remain above those for whites but….” They also write, “Since 2013 the opioid epidemic has spread to black communities, but….” Their analysis is premised on this “but.” And I’ve never seen them really address why in any meaningful way.

Despair is the complete absence of hope. I believe that despair is real, and that it’s killing people. I also believe that a better world for all of us is possible. But we have to build it together. And that is our great hope.

A broad misunderstanding about suicide in our society is that it’s a rational/well considered choice. I think talking about deaths of despair, it adds to this idea that suicide “makes sense” for the people who are dying by it. In reality most suicides are about a temporary spiraling and considered for about 15 min to hour before taking action. They’re more about the environment than anything in terms of the outcome (survival versus death). The key determinant is whether you have a gun handy during your momentary crisis or not.

America’s drug and health care system is deregulated? Tell that to the chronic pain patients who can’t find a pain management practice or get any medication due to CDC “guidelines,” and state medical boards that can ruin a physician for prescribing “too much.”