Drug ODs spiked in Norway during Covid, and they did something about it!

A new study compared overdose deaths in America and Norway during the height of pandemic-related societal disruptions. What can America learn?

I’ve been covering drugs and the overdose crisis for well over five years now. Part of the reason I started pitching news and feature stories about drugs and policy in the first place is because I noticed a major lack of research/evidence in journalism about the topic. News stories not only promoted the same old regressive ideas, they also contradicted vast bodies of evidence and deployed wildly stigmatizing language (language that elicits negative, punitive attitudes, according to research!).

Part of my mission over the years has been to push drugs out of the sensationalist “crime” vertical and instead cover it through the lens of health, medicine, science, and human rights (lenses themselves that are, to be sure, also fraught). Shining a spotlight on new research is an extension of what got me started on this beat years ago.

Welcome to Research of Substance, our series highlighting important, controversial, and hopefully useful empirical studies. Each of these posts will feature a research paper that I find interesting, spell out its gist, why the findings matter, and how the research questions factor into broader debates and discourse. Sometimes I’ll feature a couple research articles, other times I’ll only focus on one and go deep into it.

Finally, one of my biggest pet peeves is when a news story cites a study but neglects to share the damn link. I will ALWAYS share the damn link. (p.s. If the article isn’t open source and you want to access it, just reach out). Hope you enjoy my dive into a new study comparing overdose deaths in the U.S. and Norway.

“Increases in Drug Overdose Deaths in the United States and Norway During the Covid-19 Pandemic”

Published February 4, 2022 in the Scandinavian Journal of Public Health by Joseph Friedman and Linn Gjersing; access article here.

You know the types. They love to talk about the crushing nature of American life under winner-take-all capitalism. Such types tend to extoll the virtues of Nordic countries like Finland, Denmark, and Norway, countries with robust social welfare states, free health care, high living standards, and regularly rank in the tippy-top of happiest places in the world. I’m precisely that type of person, and that’s why I was so eager to check out this study. How did the pandemic impact overdose deaths in these two very different countries? And am I right to think the grass is greener in these Nordic countries?

What the study found…

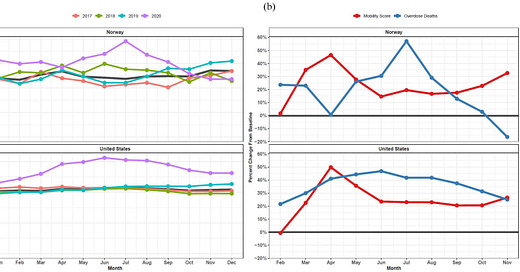

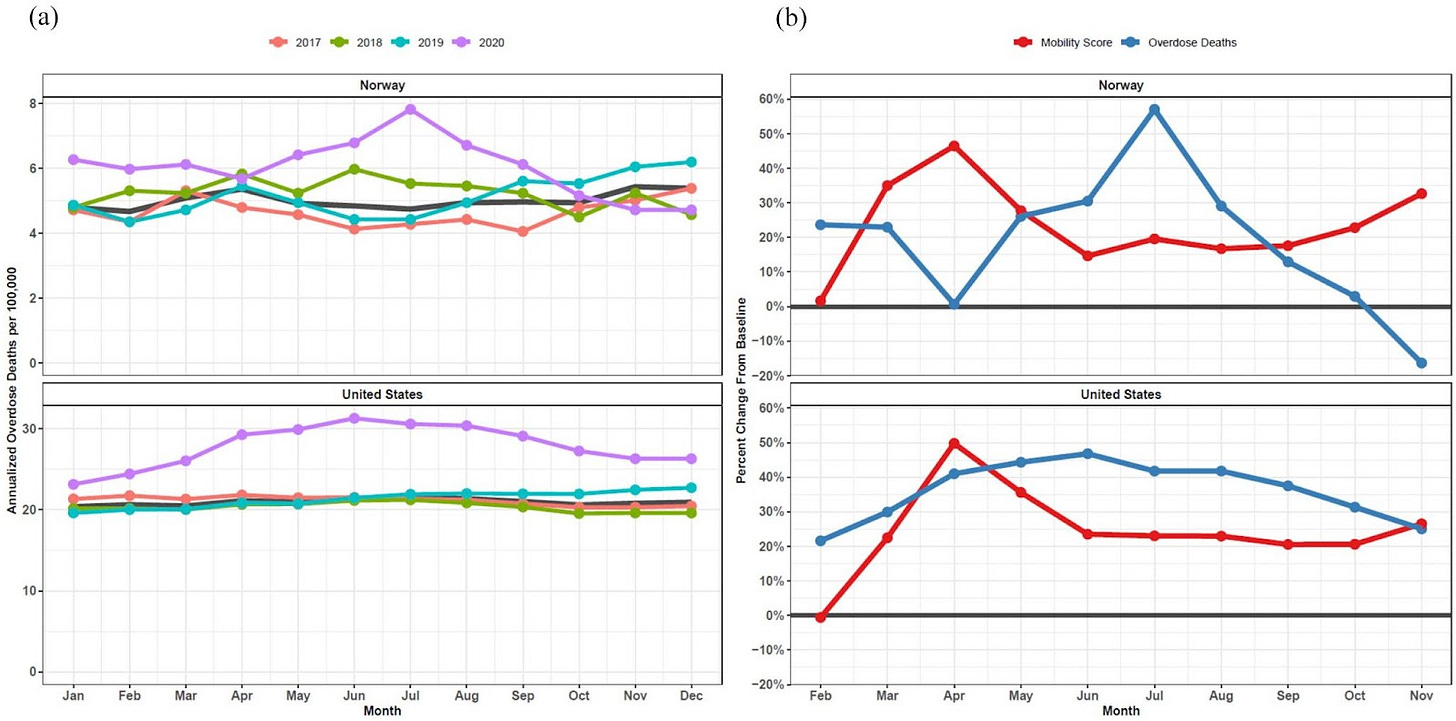

In 2020, both Norway and the U.S. saw the highest overdose-related mortality in recent history, right as countries implemented measures on the ground to slow down the pandemic. America saw a 46.8% spike in overdose deaths above baseline and Norway saw a whopping 57.0% spike in overdose deaths above baseline.

The researchers then used cell phone-based mobility data as a proxy for societal responses to the pandemic, like disrupted travel, shuttered health care services, and reduced human interaction. What’s especially noteworthy is that overdose deaths peaked both in the U.S. and Norway in the 2-3 months following significant reductions in mobility. In other words, a few months after society shutdown and we sheltered in place, overdose deaths spiked. Put yet another way, a sharp spike in overdose deaths spatially and temporally coincided with pandemic restrictions on movement.

Lastly, the study found both America’s and Norway’s spike in overdoses were pretty rough in those early days! To be sure, America has a far higher baseline rate of overdose deaths than Norway. While Norway saw a bigger jump, it also saw a much more rapid return to baseline than America. (we’ll drill down on this in a moment).

The figure below shows these results quite clearly: On the left (a), the purple line represents overdose deaths in the year 2020. See the spike come a few months after March. And on the right (b) the mobility score (red) dips sharply after pandemic restrictions, right as overdose deaths (blue) take a big jump.

What’s at stake? (In this study, A LOT)

Throughout the pandemic there’s been a raging discourse about “lockdowns.” The notion that “the cure is worse than the disease”— meaning the social and mental health impacts of shelter-in-place orders and social isolation cause more harm than the virus itself. Anti-lockdown proponents argued that isolation would cause more drinking, more suicides, more overdoses, and other harmful behaviors. While pro-lockdown advocates viewed the societal benefits of shelter-in-place orders as outweighing these other harms. After all, advocates argued, many, many, more people would die from Covid than overdoses, drinking, suicide, etc. had society remained open for business.

Now that I set up the ferocious partisan sides to the lockdown debate, let’s immediately destroy them. Because I’m not a goldfish brained political reporter who thinks it’s their job to reinforce artificial battle lines of The Discourse by hiding behind the false objectivity of “both-sides” journalism. It’s very important to take into account the consequences of any policy, but it’s also very important to make rapid decisions in response to a crisis, and hope for the best.

It’s actually very possible to think, as I do, that shelter-in-place is an important public health measure during a global pandemic, and that it’s extra important to have contingency plans in place that can account for vulnerable populations during a time of radical social disruptions. For instance, the public health experts, harm reductionists, and drug users I regularly speak with know that isolation is deadly for people who use drugs, and that more people die from overdoses when they use alone. Hence why so many of them are huge advocates for interventions like supervised consumption sites. And these findings—that social isolation leads to more overdose deaths—certainly put wind in the sails for interventions like consumption sites.

But wait, you ask, doesn’t Norway have much better health care for people who use drugs than the U.S. does? Doesn’t Norway have harm reduction services like supervised consumption sites? And what about universal free health care? Doesn’t that mean drug users in Norway can more easily access life saving medications like methadone and buprenorphine? Doesn’t all this mean Norway should’ve done much better than the U.S.? Yes, all that is true, and it is reflected in the study’s results.

After the 2-3 month window following society’s shutdown and reduced human interaction, both countries did see an overdose spike. But Norway also experienced a “more rapid return to baseline” and also saw “much lower overdose deaths” overall compared to the U.S. That’s because Norway does have consumption sites, Norway does have universal health care, and therefore, much easier access to life-saving medications. Norway also had much better Covid containment in general, and health care services were disrupted for a much shorter time. Norway also did some other interesting things I think the U.S. can learn from:

“A series of responsive actions were taken by Norwegian governmental organisations during spring and summer 2020, including weekly meetings with user organisations representing PWUD. These led to an awareness of concerns in the PWUD community and the ability for swift actions.”

Norway’s government was aware that its population of drug users were put at risk by disruptive pandemic policies. And the response wasn’t perfect, clearly, but efforts were at least made to find a way to mitigate harm during the height of Covid.

The study’s authors also recognize that America did loosen regulations on medications for opioid use disorder, but “efforts to prevent overdose deaths were scattered and underfunded compared to what occurred in the Norwegian context.” Lastly, the study’s authors suggest America’s exceptional rate of incarceration may have also exacerbated the magnitude of the overdose spike during Covid.

The study’s limitations…

This study was retrospective (looking backward) and therefore observational in nature. That means, much more hardcore mathematical methods coupled with extensive interviews of overdose survivors would be necessary to parse out causality and show a clearer picture of what happened in 2020 that led to the OD spike.

So, the timing of the overdose surge in both countries coincided with increased isolation related to pandemic restrictions. But one cannot yet say it’s because of those restrictions that this surge in overdose deaths occurred. Basically, it’s tough to pinpoint exactly which part of Covid-19 disruptions caused this overdose surge.

Still, these results raise several interesting hypotheses about what was going on in those 2-3 months after pandemic lockdowns took effect:

The first hypothesis deals with the disrupted drug supply chain: “2–3 months may be the time needed for enough of the stockpiled drug supply to be exhausted, and for pandemic-related shifts in drug supply (i.e. replacement with stronger formulations) to take effect.” So, maybe the drug supply became more potent during this time as trafficking adapted to the pandemic? (I personally think this hypothesis is the hardest to prove… the illicit drug supply is such a black box and it’s really hard to study it)

The second hypothesis deals with the stressful and uncertain nature of the lockdowns, which may have led to more chaotic and risky drug use, as the anti-lockdown crowd argued. “Supporting this notion in Norway, evidence from the two largest cities—Oslo and Bergen—indicates that the number of exchanged syringes increased during the pandemic, which may suggest higher rates of injection drug use overall;” there’s also evidence of increased drug use in the U.S.: “Nationally representative drug testing data in the US similarly showed an increase in the usage of illicit fentanyls, heroin, cocaine, and methamphetamine.” (it seems very plausible that more stress/anxiety led to more drug use when Covid first hit)

The third hypothesis suggests it took 2-3 months for health services to become maximally disrupted, causing delays in health care and emergency medical services, leading to a rise in overdose deaths. As Covid surged and stretched the capacity of health care services (e.g. fewer available ambulances to respond to overdoses) patients with opioid use disorders may have struggled to find care. In Norway, supervised consumption sites were also closed for several months, “aligning with the peak in overdoses during the pandemic,” according to the researchers. (to me, this sounds very plausible)

Of course, some mix of all these hypotheses could be behind the OD surge.

Final takeaway…

Even a country like Norway—with its high quality social and health services freely available to everyone—saw a significant spike in overdose deaths after pandemic lockdown measures took effect. So, do I still think the Nordic way of life is vastly superior to America’s “small government” society that leaves people fending for themselves? Yes, of course. A generous welfare state once again seems to create a demonstrably healthier population and lower mortality.

But there’s still some important takeaways from the fact that yes, even Norway struggled to prevent overdoses during the height of isolation caused by the pandemic. It goes to show just how complex this problem is, how much resources and attention it needs, and how long of a way there is to go to prioritize this population.

I agree with the study’s authors, who suggest that “further contingency plans for maintaining the safety of [people who use drugs] are needed during chaotic and systems-disrupting events.” When the next pandemic hits, hopefully we’re much more prepared, and that people with life-threatening illnesses, co-morbidities, and who are otherwise marginalized, can still access vital services during a global pandemic.

Finally, 2020 was brutal for overdoses around the world. It’s incredibly sad, because opioid overdose deaths are especially 100% preventable (get naloxone!). Addiction and drug use has for way too long been way too far down on the list of government and medical priorities. This population should not be swept under the rug, nor be a mere afterthought when disaster strikes.

Welcome to ‘Research of Substance.’ This is the first installment in an ongoing series that will highlight important, controversial, and, hopefully, illuminating research in the field of substance use, drug policy, harm reduction, and criminal justice reform. If you’re a researcher who regularly publishes scholarship in these fields, reach out to me on Twitter @ZachWritesStuff, send me your papers!