I’m in Sofia, Bulgaria, sitting at City Garden, a bright park overflowing with greenery and tulips. I’m with my friend Hamada, a refugee from Idlib, Syria, communicating through a mix of: his rudimentary Bulgarian; my embarrassing Bulgarian which somehow has a valley girl tilt; a hectic Google Translate combination of Bulgarian, English, Arabic, and, pantomime.

He’s cheerful, with an easy laugh, but his days aren’t easy. He barely speaks the language. He’s looking for work as a hairdresser but can’t get a job at a Bulgarian barber shop. He does as much construction work as he can get, but is hindered by his severe asthma and the fact that in the winter the countless places his body still holds shrapnel swell up and hurt.

And just like everywhere else in the world—with the exception of a minority of people who can, well, think rationally—people here view refugees with mild to extreme distaste. Britain is being roiled by anti-refugee riots. Donald Trump is working overtime to make Kamala Harris the face of the refugee “crisis” (as I tiresomely point out again and again, it’s not a “crisis” that brave, hard-working people want to come to your country). Harris, in the way of Democrats since time immemorial, is trying to outflank him on the issue by touting her “tough cop” bona fides. “I just want to find work,” he tells me, as I’ve heard countless other refugees say.

***

Hamada was studying to become a doctor when the war started.

On a sunny day in October 2014, he was sitting in his living room watching The Lost Estate on TV. It’s a Syrian comedy set in a small village, rife with hijinks over, say, the new cow, as well as subtle undercurrents of political commentary: in one episode all of the villagers are arrested in the middle of the night and they don’t know why.

He was just chilling out, watching the show, when her heard a loud explosion.

“Boom!” he says, jerking his body. Carried back to that day, he looks like he’s about to start hyperventilate in the sunny park.

“The roof fell on top of me. Then I just fainted,” he says. One of Assad’s missiles had leveled the neighborhood.

He woke up in the hospital, face covered in burns, with shrapnel lodged over his whole body. The doctors picked out the small fragments. They tried to take out the pieces in the right side of his gut and his head, but they were too large and they’re buried there still.

***

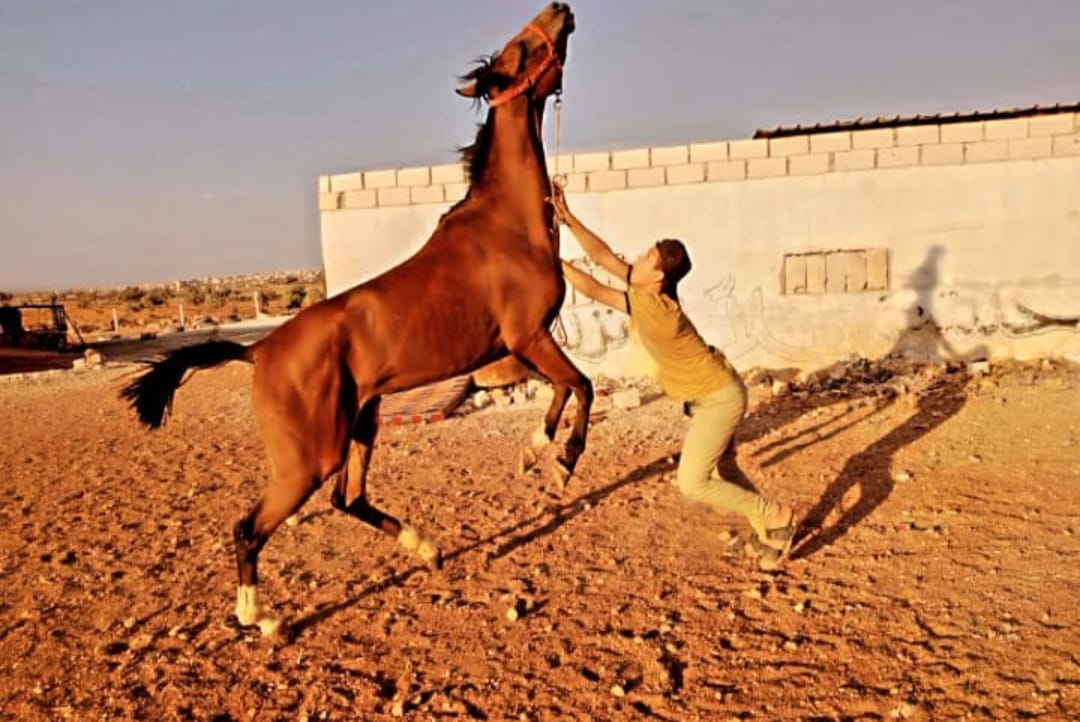

Before the missile, whenever he wasn’t studying medicine, he helped out on his father’s farm, where he loved to ride horses, as he’d been doing for years.

“I was 13 years old when I decided to learn to ride,” he says.

“I fell a lot!” he says.

. By 14, he mastered the sport.

***

The 2014 strike destroyed the house. His father had to sell the farm. The family moved into a tent. Food was expensive so Hamada quit medical school and took on odd jobs to support the family, including as a barber.

But, it wasn’t enough. By last year, he and his family had cobbled up enough money to pay for him to be smuggled into Turkey, and then Bulgaria, where he turned himself in to police and went to jail, where the doctor denied him his asthma medicine, pending a bribe, with money he did not have.

He heaves as he describes the asthma attacks he had to breathe through in a shitty Bulgarian jail for refugees without an inhaler. His father, mother, sisters, and little brothers are still in Idlib, where bombs still fall. They rely on him to send back money and he doesn’t know what to do.

***

Having reached my limit of horrid unjust tragedy, I chirp in annoying American-ese, “Someday you can still become a doctor?!?!?!!!!!!!!”

“Kak? Kak?” (how?). He shrugs his shoulders. “No. No. Never going to happen.”

I shut my dumb mouth.

My Bulgarian cousin is a doctor. Once he was accredited, he moved to Berlin. There’s a shortage of young doctors in Bulgaria. Can you imagine a world where, instead of treating refugees like terrifying intruders, the EU, say, funded language classes, and professional classes for young people fleeing a war they had nothing to do with starting?