Sam Quinones is Wrong

On a recent episode of "WTF with Marc Maron," Quinones paints a lurid tale of addiction in America. His brash and hyperbolic writing style misleads his audience.

The other day I got a concerned ping. Someone alerted me that Sam Quinones, bestselling author of Dreamland and more recently The Least of Us, two books about America’s overdose crisis, appeared as a guest on Marc Maron’s podcast, “WTF,” which reportedly nets 55 million listeners per year.

Tens of millions of people could be hearing this conversation so I felt like I had to tune in. Before criticizing and arguing with Quinones and his takes on addiction, neuroscience, homelessness, drug policy, etc., I want to be up front about my views.

It’s not like Maron or Quinones have any idea who I am. They’re both really successful guys in their late 50s / early 60s. They’d have to look pretty far down from their perch to spot me. At least that’s how I see it. So what I’m saying is: None of what follows is like, a personal beef. I just vehemently disagree with the arguments Quinones lays out in The Least of Us, his new-ish book about methamphetamine, street fentanyl, and how these drugs interact with mental health and homelessness.

I think Quinones caricatures addiction to hyperbolic extremes, I think he simplifies complexity, I think his rhetorical style is brash and lurid, and that his penchant for flowery language conceals a weak and confused argument. I think his work communicates a dark and pessimistic view of addiction. I also think it generally holds true that when writers rely on bombastic, bloated, lofty language that they’re generally full of shit, and full of themselves.

Below is an example of Quinones’s bad writing on addiction, highlighted recently on Twitter by Substance-friend and UCLA researcher Joseph Friedman. This is par the course for Quinones, who deploys a quasi-anthropological gaze upon “the addict” as some peculiar and distant species of human. It’s a totalizingly bleak view of humanity.

Style criticisms aside, there’s also important and substantive policy implications. He is looked to as an expert on matters of drug policy. He gives hundreds of talks across the country each year. In 2018, he testified before Congress as the single witness called upon to discuss the overdose crisis, a public health emergency that rarely gets attention from politicians, aside from the mealy-mouthed “bipartisan” platitudes, which as of late devolved into demagoging on border security and immigration.

Maron, on the other hand, I care much less about. He’s a comedian who I just don’t find that funny. I know of him because he’s in recovery, so naturally he’s drawn to the subject and I’ve heard him talk about it (the last Maron episode I listened to before this was when he interviewed Hunter Biden). Maron’s take on all this stuff is fairly traditional and mostly rooted in the 12-steps of Alcoholics Anonymous. It’s not surprising that he would latch on to some of the ideas in Quinones’s books, mainly around the cartoonish neuroscience of addiction and the caricature of drug users as anti-social zombies enslaved by chemicals.

Junk Neuro-babble

I’d say my first big gripe is the silly way Maron and Quinones talk about the neuroscience of addiction. Here’s a snippet of their conversation:

Quinones: So we have all these things that are hitting our brains. Not just heroin,

Maron: Right!

Quinones: Sugar. All this stuff, all these…

Maron: Your phone!

Quinones: The phone! I could go on and on about that too. And it's all hitting our brains in the same way heroin is. Maybe not as powerfully, and with such intensity, and certainly not with the intensity of fentanyl, but nevertheless it's hitting the same receptors. It’s creating that that kind of response in us to crave and that's why…

Maron: Is it the dopamine receptor?

Quinones: Yes, exactly. The opioid receptors that then generate dopamine and you want, ‘Oh! That's good. Keep doing that. Keep doing that.’

Maron: Right and you explain in the book, too, that the serotonin is the balance….

So they go on like that for a while, talking about this “tug of war” between brain chemicals and yada yada. It’s very much in the vein of the not really real “chemical imbalance” idea of brain chemistry. This stuff always annoys me. It’s a very dated view of the brain.

The real action with opioids is not dopamine, it’s endorphin, which is a combination of the word endogenous and morphine. Our brain produces what are called endogenous opioids, like endorphin, and these hormones and neurotransmitters play many crucial roles throughout the nervous system. Heroin, fentanyl, etc. are “exogenous” opioids, as they are introduced into our systems, crossing the blood-brain barrier. Science has discovered that exogenous (heroin) opioids actually imitate and mimic our endogenous opioids (endorphin).

The endogenous opioid system rarely gets discussed in these conversations, while dopamine gets all the attention. Dopamine gets pegged as this Bad Guy neurotransmitter, but it plays many important roles in our body, and having too little concentration of dopamine is the cause of horrible diseases, like Parkinson’s. There’s an excellent piece in The Gaurdian that breaksdown “the unsexy truth about dopamine,” and jokingly refers to it as the Kim Kardashian of neurotransmitters.

I think a lot of people, perhaps especially older men who fancy themselves Smart Guys, use this neuro-babble to dress up their complaints and grievences about the modern world a la phones and sugar and kids these days. This “neuroscience” of addiction takes their discussion— ostensibly about fentanyl and meth—on a bizzare digression to chicken nuggets and crack.

Quinones: Chicken nuggets. Chicken nuggets were invented in a lab at Cornell University, by the way, it's not like a recipe that some lady comes up with some place on a farm or somewhere. And so they are 60% fat and salt, which our brains evolved for millennium, for eons to crave because we got very little of it.

Maron: Right.

Quinones: And then you combine that with the dip that's got sugar in it, right? So you dip and— oh, that's the trifecta: that's sugar, fat, and salt all in one thing. But the chicken nugget I often use, it's like it's very much like crack.

Maron: Yeah, sure.

Quinones: Well, what is crack? Well, with cocaine, coca leaf, you chew the coca leaf, and it gets you mildly buzzed. Now, you process it. You strip away all those fibers that slow the absorption and the brain and you come up with cocaine. And so bam! You're hit. Okay?

Maron: Yeah.

“WTF” is precisely right title for this.

I’m just gonna move on from this stuff because it’s breaking my brain. I also just happen to like chicken nuggets. But if you’re really worried about your nugget consumption like these guys are, there are some good plant-based ones out there. I like this brand:

“New” Super Meth and Homelessness

One of the main arguments Quinones lays out in The Least of Us is that a “new meth” on the street is a major driver of mental illness and homelessness. Quinones thinks that a “new” mode of meth production, using phenyl-2-propanone (P2P) as a precursor, has caused a mass psychosis among meth users, and that a primary symptom of this psychosis is homelessness.

Quinones: You find people descending into very scary symptoms of schizophrenia, mental illness, paranoia and then very quickly homelessness, and then encampments and all that kind of stuff, too….

He very clearly draws the causal arrows: Meth causes homelessness. But moments later, talking to Maron, Quinones reverses the arrows and says people use meth to cope with being homeless. Not only that, but he thinks there are specific symptoms of mental illness related to meth derived from P2P. He thinks P2P meth specifically causes an obsession with bicycles and hoarding bicycle parts. I’m not joking.

Quinones: …Or, you use the meth because you're now homeless and this meth does an exceptionally fine job of divorcing you from reality. And so you're really not aware, or it keeps you up a lot too…

Maron: So it even explains the hoarding like…

Quinones: Yes, right.

Maron: You see the encampments, with just, you know, mountains of garbage.

Quinones: And bicycle parts everywhere. It’s a remarkable thing, but meth this meth in particular, not the ephedrine meth so much, but this meth is really connected to an obsessive behavior. One of the obsessions that people seem to have—I first heard about this in West Virginia, not in LA—is this obsession with bicycles and bicycle parts, and taking apart a bicycle, stealing bicycles, riding around late at night because you're up all night, you're up for days. And then I begin driving around LA, and I'm beginning to realize: Holy shit! I see bicycle parts… bicycles are huge.

So, just to clear up this mess: methamphetamine is methamphetamine. There are numerous ways to manufacture meth. The are numerous precursor chemicals that can be used. But the end result, the goal, is to make the methamphetamine molecule. Meth is just meth! And P2P meth is not remotely “new.” Removing the alarmism and panic, there’s material explanations for the stuff Quinones thinks he’s seeing.

One of the main things meth does is keep people awake. People living on the street have good reason to stay awake. They worry if they fall asleep they’ll get robbed and lose all their stuff. If someone is awake for too long, if anyone is awake for too long—on meth or not—they will present as mentally ill. This does not mean they are permanentaly mentally ill and have schizophrenia. It means they need to sleep.

Recently in Filter, Claire Zagorski, of The University of Texas at Austin College of Pharmacy, wrote that P2P meth dates back to at least the 1970s. Zagorski then skewers Quinones’s core argument about the “new meth” being a primary driver of severe mental illness:

“Quinones claimed that separating the two isomers is “tricky, beyond the skills of most clandestine chemists,” but that it seemed “the criminal world” finally figured it out around 2006. Thus, a boom of unprecedentedly pure meth—high D, low L—compared to the so-called less pure P2P meth of 50 years ago.

Of course, what he’s essentially describing is pharmaceutical-grade meth, the regulated version of which is sold under the brand name Desoxyn. But it’s easier to for an article to paint something as “sinister” if it leaves out that there’s an FDA-approved prescription form that doesn’t cause “cerebral catastrophe” which “always [involves] violent paranoia, hallucinations, conspiracy theories, isolation, massive memory loss, jumbled speech.”

This is quite damning for the thesis of Quinones’s book: A “new meth” is what’s really behind mental illness and homelessness. It happens to be the same bunk argument that animated Michael Shellenberger’s failed bid for California Governor. Remarkably, Quinones also concludes that giving people access to housing doesn’t actually help address homelessness.

Quinones, just like Shellenberger, argues against Housing First policies (which have been thoroughly studied and are highly effective):

Quinones: The idea that took hold at the same time, as these policies, and at the same time, as the meth and then the fentanyl were spreading all across the country, was that: Housing is the problem of homelessness, and that all people need is a house. Which I think has shown itself to be absolutely insane. You know, take a person off of the street, that's the idea, and put them in a house with services, with a case manager, and all that kind of stuff, and that person, no matter the state of mind, will be better off.

What ends up happening is of course, they can't handle it. They don't like it. They begin to tear the place apart. That's what we're finding in LA. I think a lot of landlords will not rent to…

Maron: Because they bring the street into the house

Quinones: And they frequently just shred the house. You know, because they're not prepared. It's not an idea that you can just go from the street to a perfectly nice house and have the mental wherewithal to and preparedness and stop the drugs….

Perhaps Quinones purposefully does not name the policy he’s arguing against. Surely he’s seen the many years of research evidence that supports Housing First. But that evidence seemingly doesn’t gel with his own view of homelessness or the story he wants to tell. Perhaps the outcomes from Housing First do not comport with what he’s witnessed himself on the street.

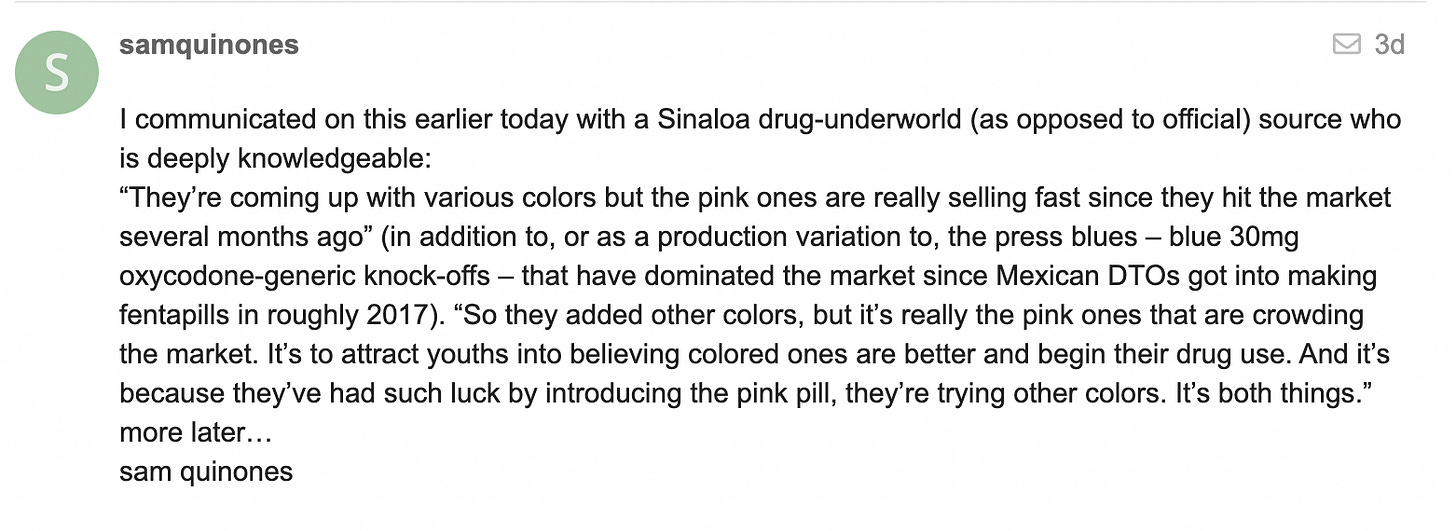

As I’ve come to understand to him, Quinones places his own experience as a journalist above other, more rigorous, types of evidence. If a source tells him that drug traffickers are trying to lure the youth as new fentanyl customers by selling pink colored pills, he will believe it. There’s a certain credulity when it comes to confirming his thesis.

L.A. Noir

This all gets to my critique of Quinones’s style as a writer and journalist. The way he positions himself as a reporter is as though he’s in the middle of a frightening noir. Only he can connect all the dots and blow the lid. Listening to him talk, and reading his books, Quinones is first and foremost a storyteller. He’s a natural narrator. To be sure, he’s good at it. This kind of storytelling takes a level of talent to execute. His non-fiction books about the overdose crisis are bestsellers for a reason: They read like a true crime thriller.

I tend to like this narrative style. I love conspiracy thrillers and noir. But applying this style to a public health emergency like the overdose crisis causes some problems. For one, there’s a lot of overlapping dynamics that do not flow linearly. I’ve found the complexity of the North American overdose crisis to be narratively difficult to handle. This is especially the case for the illicit drug supply, which is a black box due to the fact that, unlike licit and regulated markets, there is not a lot of solid quantitative data out there. We have very little macro supply chain metrics. Drug traffickers are not publicly traded companies that share data. There’s no Bloomberg Terminal for the drug supply. There’s mostly a lot of anecdotes, cross-sections, and snap shots.

A lot can get projected onto this black box. Once Quinones sees the arc of a story take shape—a new super meth!—suddenly everything he sees slots right in and confirms the thesis. From totally banal things like chicken nuggets, bicycle parts and a precursor chemical. This is a very natural function of human psychology. We’ve got confirmation bias, which is pretty self-explanatory. And there’s also apophenia: The tendency to perceive a connection or meaningful pattern between unrelated or random things (objects or ideas).

To better understand Quinones’s style, it helps to understand the journalistic milieu that he came up in. He was a journalist at the Los Angeles Times from 2004 to 2014, where he covered immigration and gangs. The LA Times innovated a gritty style of crime journalism that produced some killer investigative work. Times journalists wrote incredible exposés detailing brazen systemic corruption within the LAPD, leading to the Ramparts Scandal within the Community Resources Against Street Hoodlums (CRASH) anti-gang unit. These were dirty, crooked cops that inspired movies like “Training Day.”

Quinones left the LA Times to freelance and write Dreamland, his first book about the overdose crisis that tracked the market shift from oxycodone to heroin. This book put Quinones on the map. The timing was perfect and the book landed in a big way that his previous books did not. So Dreamland was published in 2015 and the LA Times started publishing their big exposé of Purdue Pharma a year later in 2016. This may have been a little awkward. Quinones kinda scooped his former colleagues. (One of the reporters on the LA Times team that did the Purdue investigation was Scott Glover, who was my investigative journalism professor at USC in 2016-2017).

This investigative tradition, especially about corrupt cops, is still alive today at the LA Times, where its journalists are a thorn in the side of Los Angeles County Sheriff Alex Villanueva, who was straight up targeting an LA Times journalist named Alene Tchekmedyian for exposing a cover-up.

Quinones was coming up as a crime reporter in California during the era of L.A. Confidential, true-crime, and Ramparts investigations. Los Angeles was home to this noir-ish style of crime journalism. Stories like these almost always feature a man at the center of a vast conspiracy, bumping into sketchy “underworld” characters involved in mysterious and corrupt dealings. Noir also tends to hold a bleak, pessimistic view of human nature. People are corrupt, can’t be trusted, prone to vice. Lots of noir stories have characters like sex workers and drug users who are often portrayed as hapless, chained to their vices, in need of a savior. Theyr’e pitiful, tragic figures.

I think this style is especially apparent in how Quinones portrays people who use drugs. According to his view, these are people who need to be saved for their own good, people who are enslaved, whose drug use has perma-fucked their brains, creating a world of delusion, condemning them to live among filth on the street. It’s a pretty bleak, pretty brutal, extreme portrayal of drug use. And I get it. I think fentanyl is a particularly grim type of addiction. The physiology of it is brutal. Meth, too. At least it can be. But that’s not always the case for everyone.

The true nature of addiction, of course, is much more complex than this gritty noir narrative allows. There is a huge spectrum of drug use and addiction out there, and only a small, tiny portion of drug users wind up in the dire circumstances you see in Los Angeles’s “skid row.” If you look hard at how and why people got there, it’s very unlikely that it’s because a drug trafficker somewhere in Sinaloa switched up the precursor used to make meth.

Los Angeles’s “skid row” has been a “containment zone” since the 1970s, and decades of crackdowns and “cleanup” plans have failed. This problem has been going on for so many years. It precedes meth and fentnayl. It’s not farfetched to think synthetic drugs can make things worse; arguing drugs as the primary or even secondary cause is wrong.

What Quinones thinks about addiction and homelessness actually matters. Politicians and policymakers seem to like what he’s saying: These new scary drugs are bad and they’re causing homelesness. A lot of what Quinones says happens to line up with how law enforcement views their job in the context of addiction. They cling to success stories, graduates of a drug court, the people who say they never would’ve have recovered had they not gotten arrested and locked up. In 2017, Quinones wrote a New York Times op-ed arguing for precisely this: “Addicts Need Help. Jails Could Have the Answer.” (Arresting people with opioid use disorder drastically raises their risk fatally of overdosing).

Talking to Maron, Quinones laments that police in Los Angeles lack the power and authority to seize and destroy the property of unhoused people. He laments that it’s difficult to violate people’s civil liberties through involuntary commitment and compulsory “treatment.” Though that may change with Governor Newsom’s “CARE court” idea, which disability rights groups adamantly oppose on civil liberty grounds.

While talking to Maron, Quinones let slip what he really thinks about people who start using drugs:

Quinones: I talked to this this gang member source I've had for a long time. A wonderful guy. Really great. I call him Timmy in the book… He was using meth. He was clean for a lot of years. His life was going great. And then, like an idiot starts using again, begins to believe that he can be some major kingpin of trafficking meth….

Listening to it, Quinones calling his “longtime” source an “idiot” for using meth again after years of recovery—it kinda slides right by. Like an idiot. It’s a common turn of phrase. It’s usually something I’ll say self-depcratingly: “Like an idiot, I waited 20 minutes at the wrong bus stop” or “Like an idiot, I listened to two hours of Marc Maron.” But this is different: Like an idiot, he starts using meth again could be nothing other than a regrettable turn of phrase he didn’t really mean. Or it could be Quinones’s own views subtly breaking through. That after all these years of investigating the causes and conditions of addiction, he thinks people who use drugs are simply idiots for doing so.

Look, there is a ton about The Least of Us and this Maron interview that I didn’t get into. A lot of what Quinones also talks about is the hollowing out of small towns across the country, reeling from the flight of capital and manufacturing. People from some of the places Quinones writes about say they don’t recognize their hometown in his words. That’s always a good tell. Do the locals feel like their home is being accurately represented? In some cases, the answer here is no.

And the policy implications of alarmism and pressing the “scare” button aren’t great either. Reviewing “The Least of Us” in The Washington Post, drug historian David Herzberg, author of “White Market Drugs,” succintly summarizes the problem with Quinones’s work:

“This poignant appeal is also where “The Least of Us” goes awry, unfortunately. To amp up the emotional wallop, Quinones leans on the hoariest myths that have long marred drug journalism: that once-proud if scrappy White communities are being destroyed by foreign traffickers selling a new generation of super-drugs that turn consumers into subhuman zombies. This sensationalist story is depressingly familiar to me as a historian of drugs, and it stands in stark conflict with Quinones’s brilliant analysis of America’s malfunctioning drug markets. The “super drug” myth is the true unkillable zombie, surviving a century of repeated debunking and wreaking its own distinctive political harm.”….

Quinones has no laboratory or epidemiological evidence that P2P meth is different from ephedrine-produced meth — the “super-meth” theory is based entirely on anecdotes.”

The bottom line is: I think Quinones’s background as a journalist covering gangs and crime infects his writing about the overdose crisis. I think it leads to some misleading, hyperbolic caricatures of drug use. This panic and fear is fuel for the drug war machine.

Update: Apparently Colorado lawmakers were listening to Quinones when they voted on misguided legislation that basically makes any possession of fentanyl a felony charge. Severe punishments for low-level drug stuff is an utterly failed response to what’s happening in the world. This is what I meant when Quinones’s bad ideas and bad writing lead to bad policy implications.

If you made it this far, thanks for reading all of this. I hope it was useful. And if you like this sort of writing and analysis about drugs, please subscribe to Substance.

Like James Ellroy's mind does crossfit

Quinones also suffers from "new" form of toxic masculinity which makes him prone to delusions.